Why Trump withdrawal from Paris Agreement is not such a bad thing

If the US stayed in the tent under Trump, its negotiators could, for example, agitate to weaken any deals struck at future COP meetings. We saw such tactics from Saudi Arabia at COP29 in Baku.

Story by Rebekkah Markey-Towler

On his first day back in office as United States president, Donald Trump gave formal notice of his nation’s exit from the Paris Agreement – a vital global treaty seeking to rein in climate change.

More To Read

- Brazil aims to rally major economies for stronger climate pledges ahead of COP30

- Major breakthrough as UN adopts plan for net-zero shipping emissions by 2050

- Why Kinshasa keeps flooding and why it's not just about the rain

- Renewable energy surges to record highs but remains off track for 2030 goals – Report

Before signing the order, Trump declared his reasons to an arena of cheering supporters, describing the global agreement as an “unfair, one-sided Paris climate accord rip-off”.

Of course, this is not the first time Trump has withdrawn the US from the Paris deal – he did it in 2017, during his first term in office.

On one hand, Trump’s move is a huge blow to efforts to global climate action. The US is the world’s second-biggest emitter of greenhouse gas pollution, after China. The country is crucial to the global effort to curb climate change.

But given Trump’s climate denialism, it’s actually better that the US absent itself from international climate talks while he is in power. That way, the rest of the world can get on with the job without Trump’s corrosive influence.

A quick refresher on the Paris Agreement

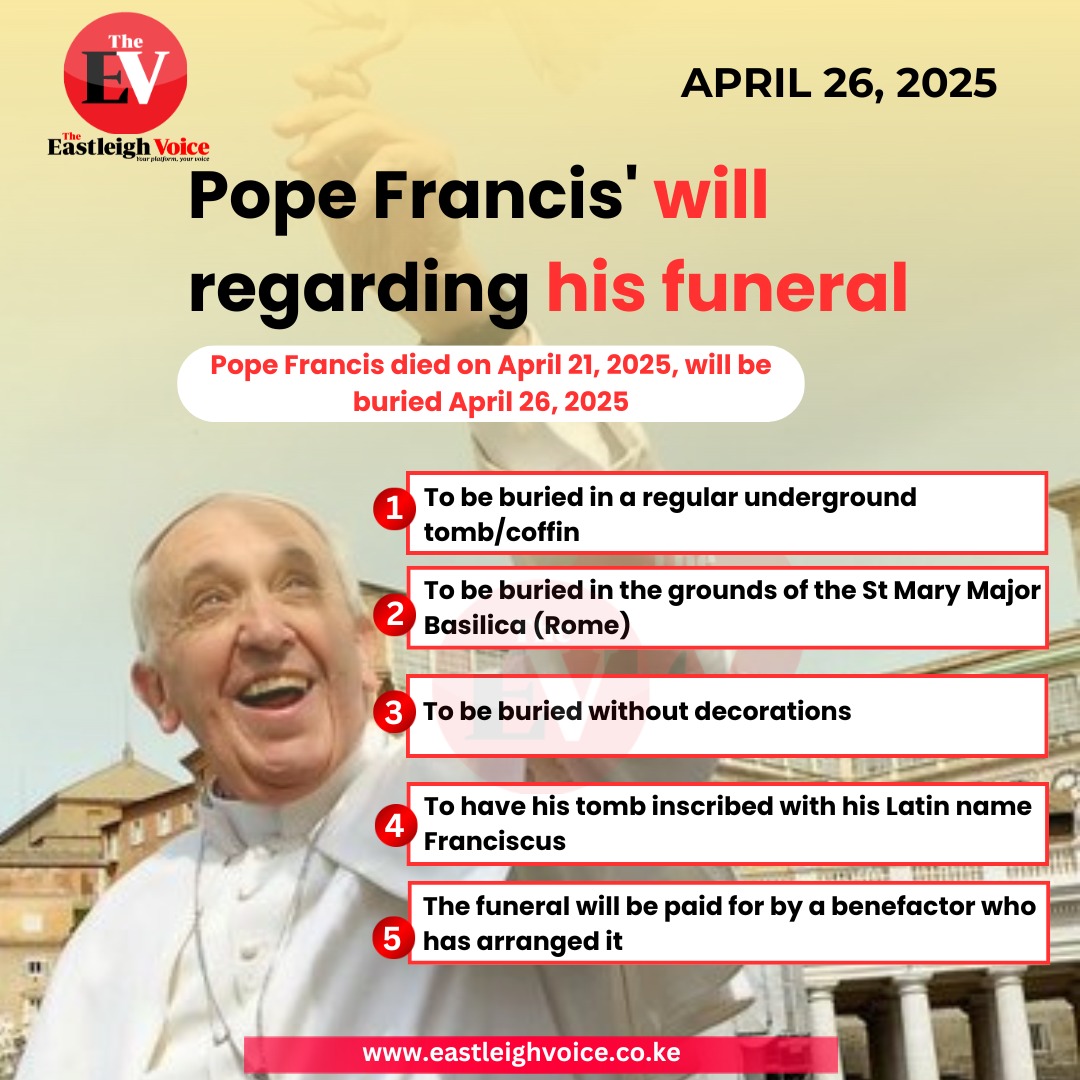

Signed by 196 nations in 2015, the Paris Agreement is the first comprehensive global treaty to combat climate change.

Its overall goal is to hold the increased global temperatures to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C.

Scientists say meeting the more ambitious 1.5°C target is crucial, because crossing that threshold risks unleashing catastrophic climate change impacts, such as more frequent and severe droughts and heatwaves.

Under the agreement, each nation must make national plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to help reach the global temperature goals. These plans are known as “nationally determined contributions”.

COP29 President Mukhtar Babayev speaks during a closing plenary meeting at the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 24, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov)

COP29 President Mukhtar Babayev speaks during a closing plenary meeting at the COP29 United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Baku, Azerbaijan November 24, 2024. (Photo: REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov)

What Trump’s withdrawal means

Under Trump’s last presidency, the US was only out of the Paris deal for four months, due to the time it took for the retreat to take effect. President Joe Biden rejoined the agreement in early 2021.

This time, the US withdrawal will become official more quickly – after a year. Then, the US will join Iran, Libya and Yemen as the only United Nations countries not party to the agreement.

The US can keep participating as a party to the Paris Agreement until January 2026. That means it may try to negotiate at the COP30 climate change conference in Brazil this year.

COP30 is a big deal. It is when each country is due to present its new nationally determined contributions. The US withdrawal means it is unlikely to bring a new contribution to the meeting – if it attends at all.

Should the US show up, its presence would potentially destabilise negotiations. That’s why removing Trump-backed negotiators from the climate talks going forward is a good outcome.

If the US stayed in the tent under Trump, its negotiators could, for example, agitate to weaken any deals struck at future COP meetings. We saw such tactics from Saudi Arabia at COP29 in Baku. The oil state repeatedly disrupted the talks and in one instance, sought to alter important text in the agreement without full consultation.

With the US out of the way, the other parties to the Paris Agreement have a better chance of progressing climate negotiations.

The women-led, international climate initiative Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) is aiming to 're-frame and redirect the narrative on climate change'. (Photo: Reuters)

The women-led, international climate initiative Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) is aiming to 're-frame and redirect the narrative on climate change'. (Photo: Reuters)

At this stage, it doesn’t appear other countries are preparing to follow Trump out the door. This is despite controversy at the COP29 talks when Argentinian president Javier Milei ordered his negotiators to withdraw only a few days in. Milei had previously described the climate emergency as a “socialist lie”.

At this stage, Trump has not withdrawn from the Paris Agreement’s parent convention, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. So after it withdraws from the Paris deal, the US can still attend COP meetings, but only as an observer.

Onwards and upwards

Of course, there are downsides to the US withdrawal from the Paris deal.

Leaving the Paris Agreement means the US is no longer required to provide annual updates on its greenhouse gas emissions. This lack of transparency makes it harder to determine how the world is tracking on emissions reduction overall.

Under the Biden administration, the US contributed funding to help developing nations adopt clean energy and cope with climate change (albeit delivering less than it promised). Trump is expected to slash this funding. That will leave vulnerable nation-states in an even more precarious position.

While the US was technically only out of the Paris deal for a short period last time, the process was destabilising. It weakened what was an unprecedented show of international solidarity and sent a damaging message about the importance of climate action.

Trump’s latest withdrawal is a similar blow to morale. It’s particularly galling for Americans fighting for climate action, and those struggling with its devastating effects – most recently, the unthinkable fires in Los Angeles.

But Trump’s withdrawal can easily be reversed by a new US president. And we can expect other parties to Paris, such as China and the European Union, to continue to play a leadership role, and others to fill the vacuum.

What’s more, as others have noted, Trump cannot derail global climate action. Investment in clean energy is now greater than in fossil fuels. When Trump last pulled out of Paris, many US state and local governments pressed ahead with climate policy; we can expect the same this time around.

And the vast majority of the rest of the world is still pursuing emissions reduction efforts.

So overall, the US exit from Paris is probably the best of a bunch of bad options. It mutes Trump’s capacity to destabilise international climate action, allowing others to step into the breach.

Rebekkah Markey-Towler, PhD Candidate, Melbourne Law School, and Research fellow, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

Top Stories Today